All babies reach milestones on their own developmental timeline. A multitude of factors influence the rate of each baby’s individual growth such as genetics, form of delivery, gestation at delivery, medical issues, effectiveness of the placenta prior to delivery, and so on.

However there is a persistent and understandable demand from first-time Mothers for information on what is considered ‘the norm’. This is particularly so with breastfeeding, as understanding breastmilk intake is more complex than looking at the oz mark on a bottle. This is a topic rife with large-scale confusion, especially as breastfeeding Mothers are in the minority and can often find themselves, and their health workers, comparing their baby with formula-fed babies.

Breastfed babies are not the same as formula fed babies. One is fed the milk of its own species; the other is fed the milk of an entirely different species, so it is unsurprising that stark differences can be observed.

What follows is a timeline detailing the journey of the average breastfed baby. I hope it will prove to be a useful and reassuring tool for new Mothers.

At Birth:

Given enough uninterrupted time skin-to-skin, your baby may move towards your breast and begin feeding without assistance.

The first feed helps to stabilize baby’s blood sugars and protect baby’s gut (NCT).

Most babies will nurse better at this time than they will for the next couple of days. Take advantage of this. “A full-term healthy newborn’s instinct to breastfeed peaks about 20 to 30 minutes after birth if he is not drowsy from drugs or anesthesia given to his mother during labor and delivery” (La Leche League). Breastfeeding in the delivery room or the recovery room after a caesarean section lays the hormonal groundwork for your future supply of mature milk.

If you experience greater than expected blood loss while giving birth or have retained placenta inside your uterus after birth, this can lead to milk supply problems.

Make sure that the midwives are aware that no formula is to be given to your baby unless strictly necessary and not without your consent.

Your baby will be weighed following his birth.

Your baby’s first feeds are about quality, not quantity. At the moment, and for the first few days after birth, your breasts are producing small quantities of colostrum (about 3-4 teaspoons daily). This is a concentrated clear yellow secretion which is high in protein, fat-soluble vitamins and minerals, as well as antibodies that protect your baby from bacterial and viral illnesses.

Because they don’t know how to breastfeed efficiently yet, newborns sometimes nurse for fifteen or twenty minutes (Gonzalez 2014).

As your baby’s mouth is so small at this age, you may need to squeeze your breast (think of holding a sandwich) so that your baby can latch on to the nipple more easily. Once your baby is latched, you can let go.

Your newborn should not go longer than three hours between feedings. However you may find that he is very sleepy for the first few days and may not be interested in feeding. If this happens, you will need to wake him up. Undressing him and giving skin to skin contact will help wake him up and encourage him to feed.

As you feed, the hormone oxytocin will help your uterus regain its tone after birth. This process also protects against excessive bleeding as you recover from childbirth. You may feel mild menstrual-like cramps whilst your uterus shrinks.

Day 1:

During your baby’s first 24 hours, he might wet his nappy only once or twice (Fredregill 2004). This is because the colostrum you produce is highly digestible and perfect nutrition for your baby, so there’s not much left to eliminate.

Over the next 24 hours, your baby will begin to increase their hunger so they are having eight to twelve feedings per 24 hours. Many babies will feed more frequently than this and it may seem as though your baby is insatiable. This is because his stomach is so small it gets full very quickly and empties very quickly. Feeding frequently is also essential to build up your milk supply, so feed on demand rather than clock watching.

Most newborns require 10 to 45 minutes to complete a feeding (Murkoff. S).

It can take a week or two for your letdown reflex to work in sync with your baby. Until then it’s likely to be erratic (Rapley and Murkett 2012). Offering your baby a chance to feed whenever you notice a tingling sensation or a sudden leakage of milk will help it begin to work more reliably.

Expect at least one or two wet nappies each day for the first few days after birth. It may be difficult to tell if a nappy is wet at this early stage, and it is normal to find pink crystal-like stains. If you are finding it difficult to judge if your baby’s nappy is wet, try putting a cotton ball in the nappy. When your baby urinates, the cotton ball will feel very wet.

During this period, your baby’s mouth is acutely sensitive to any stimulation. A dummy, bottle, or sucking on your finger stimulates your baby’s mouth differently than your nipple. A newborn can easily become accustomed to this overstimulation of the tongue and hard palate. “Confusion can occur after just one exposure to a bottle or ‘dummy’ (pacifier)” (Rubin. S). Therefore try to avoid or delay your baby’s contact with non-breast suckling until he is at least 6 weeks old.

These first two weeks are crucial for breastfeeding. Frequent and effective feeding during this time primes milk-making cells, laying the foundation for optimum milk production. In many cases where breastfeeding goes wrong, the problem can be traced to this very early period (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Day 2:

Expect at least two wet diapers today (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

From now onwards your baby should be producing at least two teaspoon-sized poos (or larger) per day (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Most babies (whether breastfed or not) will have a small amount of jaundice, which starts after the first 24 hours of birth, reaches a peak around day 3 or 4, and then gradually fades over the next week.

Frequent breastfeeding or pumping during these crucial days after birth awaken receptors sensitive to the hormone prolactin, a key player in the production of mature breast milk. If you become separated from your baby or your baby is unable to breastfeed, then pump your breasts with an electric breast pump every three hours. Pumping will send your body the message that you intend to breastfeed.

You may have heard the mantra: “If it hurts, you’re doing it wrong”. Whilst agonizing pain indicates a problem and should receive immediate attention, a moderate level of discomfort is normal during these early days as your breasts adjust to being suckled. You should feel a gentle tug that will take some getting used to.

It is not unusual for a newborn to suck for a very long time.

Your baby’s bowel movements will now change to a greenish-brown color and will look like thick pea soup. He will pass two to three stools per day. If your baby has not had a movement by the end of today, your doctor should be notified (Spock 2004).

Day 3:

Feel that you are having a tough time? You’re not alone. In a recent Pediatrics study, three days after giving birth, 92 percent of new Mothers say they were having problems breastfeeding. Half of the Mothers reported problems with getting the baby to latch on to the breast, or other feeding issues like nipple confusion. And 44 percent said pain was a problem. A further 40 percent said they felt that they weren’t producing enough milk (Pediatrics 2013). But remember, these are maternal perceptions and most likely not reflections of the physiological reality. If you find yourself in the majority of Moms and feel you are having problems, please contact La Leche League.

Day 4:

By now you will have given your baby his first – and easiest – “immunization” (antibody-rich colostrum) and helped to get his digestive system running smoothly.

Your baby will be weighed again around this point, probably at home by your midwife. He may lose between 8 and 10 per cent of his original birth weight, as he adjusts to the sudden loss of his beloved placenta. Breastfed babies, who have consumed only teaspoons of colostrum, generally lose more than bottlefed babies (Murkoff. H). This weight loss is quite normal and expected, and you should see your baby start to gain weight soon. Babies who weight more at birth may lose up to 14 or 15 per cent. High weights at birth can be due to water retention, and the excess weight is got rid of through the urine; these babies lose more weight and take longer to put it back on (Gonzalez 2014). Remember also that in the first few days your baby may be weighed on several different sets of scales, which can all give subtly different readings.

Also around this time, your milk will ‘come in’ and you may find yourself with the infamous ‘melons’ – aka your breasts swelling and becoming engorged and warm. Overabundance at this time is normal as your body learns to predict exactly how much milk your baby needs (note that if you had a c-section or are diabetic, your milk may come in a few days later than this). The engorgement usually settles down within 24-48 hours. As your baby starts to feed regularly your body will adapt to producing the right quantities of milk to nourish him. Engorgement is more uncomfortable for some women than for others and is typically more pronounced with first babies. With subsequent babies, engorgement may occur sooner. You may wish to apply chilled cabbage leaves to ease engorgement, however limit use to 20 minutes, no more than 3 times per day, as cabbage can decrease milk supply.

It is important once your milk does come in that your breasts are regularly emptied in order to stimulate and ensure a good supply of milk.

Check your breasts for blocked ducts which are more likely to occur around this time. Try to avoid wearing a bra during this short engorgement phase if possible as a bra may compress your breasts and make swelling worse.

The color of your early milk will gradually shift from yellow to white. At the moment your creamy transitional milk contains high levels of fat, lactose, vitamins and more calories than the colostrum. The photo bellow shows colostrum on the left expressed on day 4, and on the right is breastmilk expressed on day 8.

In these early days you may feel your baby’s feeding pattern is quite unpredictable, but go with it. Feed him when he wakes, for as long as he wants, until he literally drops off.

On average, feedings will take about 15-20 minutes on each side, although variations are normal. Like adults, babies can be fast or slow eaters. Flow can also vary among mothers: some have a fast flow or milk, while others have a slower flow, making feeding last longer.

Your baby may take only one side at a time but it is wise to offer both.

If you are not happy with how things are going, get help early. It’s easier to correct problems early than to be re-building a milk supply next week. I recommend speaking over the phone with a La Leche League leader or attending a La Leche League meeting.

As a result of your milk coming in your baby will start passing soft mustard-yellow stools (or orange and even green can be normal). At this stage at least one nappy per day should be full of poop and a mess to clean up. This ‘explosive poo’ phase will continue for a few more weeks.

Whereas in the past few days it may have been difficult to tell that your baby’s nappy is wet, now his nappies should be undeniably wet, however the urine should have no strong color or smell.

Your baby should be producing at least six pale yellow wees every day (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Most babies of this age spend an average of 187 minutes per day nursing during their first two weeks of life (Fredregill 2004).

Smaller babies tend to eat more frequently than bigger babies (Spock 2004).

You may now be feeding around a dozen times over 24 hours. Soon, you will build up to around 20 minutes per feed every two to four hours. Fear not. This frequency is only temporary, and as your milk supply increases and your baby gets bigger, the breaks between feedings will get longer. Mothers who are particularly anxious to make a success of breastfeeding are apt to feel disappointed by this frequency on the assumption that it means the breastmilk supply is inadequate. This is incorrect. The baby has now settled down to the serious business of eating and growing and is providing the breasts with the stimulation they must have if they are to meet the increasing demands.

Day 5:

Feeling tired? Night time waking is the result of healthy biology. During these early weeks breastfed babies are hungrier at night than during the day. Your newborn’s hunger naturally corresponds to the rise of your breastfeeding hormones after midnight. These late-night feedings serve to help you to build a strong milk supply. Over time, the situation will evolve, and your baby will sleep more at night and be awake for more hours during the day.

The frequency of your baby’s feeds is likely to reach a peak today. After this, things will gradually settle into a pattern. Some feeds will be long, others just snacks (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Your nipples may be slightly sensitive during these first few days – a few seconds of ‘ouch’ at the beginning of a feed isn’t unusual – but that’s all. After that, the feed should be pain free. This preliminary soreness should resolve itself by day 10. Pain that makes breastfeeding intolerable and /or cracked and bleeding nipples are never normal and needs immediate attention from a health professional familiar with breastfeeding management.

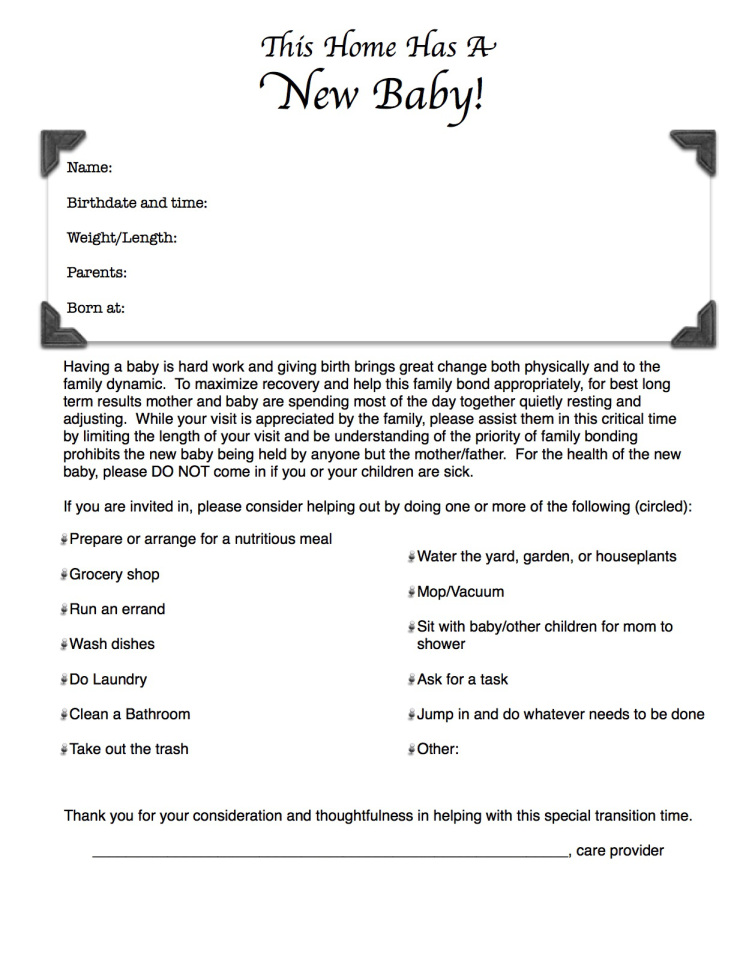

During these early days you may find relatives and other well-wishers offering to “take the baby off you while you rest/ buy groceries/ get on with the housework”. What would be more helpful however would be to hear: “let me do some housework for you while you get on with nursing and bonding with your baby”. For a not-so-subtle hint, print THIS and put it on your fridge or in another prominent place.

You may notice your baby has a ‘nursing blister’ on their top lip. These are painless blisters that often form on a baby’s lips in the early days and weeks of breastfeeding. They are a harmless sign that your baby is feeding well, and they will soon fade.

Your baby’s bowel movements will now change to a loose, mustard-yellow, cottage-cheese or seed-like consistency. These are called milk stools. Your baby will pass two to five stools per day, most probably during a feeding.

Your baby has now received five million cancer-busting stem cells from your milk (Williams 2013).

1 Week Old:

Your baby will tend to gain weight steadily as your mature milk supply is established. Once your baby is regularly gaining weight, it is no longer necessary to wake them to breastfeed. Simply follow your baby’s lead.

Expect your baby to now gain around 4-7 ounces (112-200 grams) per week for their first month.

At this point your breasts may feel full but soft. You may frequently leak breast milk and begin wearing breastpads. However note that leaking has no relationship to how much milk you’re making.

Young babies, both breast and formula fed, are often fussy. This fussiness starts at around 1-3 weeks, peaks at around 6-8 weeks and is gone by 3-4 months. “They want to be ‘in arms’ or at the breast very frequently and fuss even though you attempt to calm them. They often seem ‘unsatisfied’ with their feedings and even seem to reject or cry at the breast” (Mother to Mother). It is not unusual for fussiness to happen during the late afternoon and evenings, and is usually NOT due to hunger, wet/dirty nappy, or anything that you can remedy. It is usually NOT related to milk supply, although some Mothers worry about this.

By the end of this week your transitional milk will have turned into mature milk which is thinner and contains more water. It consists of 90 percent water and 10 percent of carbohydrates, proteins and fats necessary for both growth and energy. There is more watery high-protein milk at the start of a feed, gradually gaining higher levels of fat as you go through the feed.

2 Weeks Old:

Most babies have regained their original birth weight by this age. If this is the case, the frequency of weighing should reduce. Note that there is no compulsory requirement to get your baby weighed. UK Government guidelines state that weighing can occur “if parents wish, or if there is professional concern.”

If your baby has yet to regain their birth weight, try not to worry, “it can take up to three weeks” (La Leche League). Encourage your newborn to breastfeed frequently during the day as well as during the night. Also wait until your baby has finished feeding from the first breast before offering the second. This way, you can be sure that your baby is getting to the rich, fatty hindmilk.

You are likely to also notice your baby’s first growth spurt around this time. This means that your baby will actively return to the breast many times for closely linked ‘cluster’ feedings. Typically, this pattern occurs during the late afternoon or evening hours. Growth spurts generally last 2-3 days, but for a few Mothers they can last a week or so. This is normal, healthy behaviour and NOT a sign that you have an inadequate milk supply.

By now at least one nappy per day should be thoroughly soaked.

Although sucking is a newborn reflex, the mechanics of effective latching on aren’t. It usually takes a couple of weeks, and sometimes longer, for Mothers and babies to get really good at nursing.

Does your baby have jaundice? So-called ‘breastmilk jaundice’ is much less common than newborn jaundice. It doesn’t normally appear until now. Unlike a baby with newborn jaundice, the baby with breastmilk jaundice is alert, asking for feeds frequently, weeing and pooing normally and gaining weight. So, although it can last for several weeks or even months, this type of jaundice doesn’t usually need any treatment (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

3 weeks old:

You have reached the stage where your baby will probably have a little neck control and a decent latch which makes this the perfect time to practice the lying down breastfeeding position. Once mastered, this position will greatly aid night time feedings as you can snooze whilst your baby helps himself.

Your nipples ‘toughen up’ after 2 to 3 weeks (Cave and Fertleman 2012).

You probably feel as though you have done nothing but feeding. However by now you and your baby will be getting to grips with the practicalities of feeding and leaning to trust each other. It may not feel like a huge milestone but by focusing on breastfeeding for these first three weeks you have set up your long-term capacity to produce as much milk as your baby needs and laid the foundations for an easy breastfeeding relationship.

1 month old:

“By around week 4 your baby will take around 40 minutes to feed, rather than an hour” (Cave and Fertleman 2012).

Your baby’s weight will probably start to slow down a little from his previous rapid gain. Expect your baby to gain an average of 1-2 pounds (1/2 to 1 kilogram) per month now until 6 months.

Your baby’s poo production will also slow down. She may go for several days (maybe even a week or more) without producing a poo at all. This is quite normal at this age (Rapley and Murkett 2012). Other breastfed babies may pass several per day. It depends very much on the individual. Infrequency is not a sign of constipation. Hard, difficult-to-pass stools are. Constipation is very rare in breastfed babies.

Your baby will grow in length by about an inch per month (2.5c.m.) until 6 months.

As babies grow older, they not only gain more slowly, they also gain more irregularly. Teething or illness may take their appetite away for several weeks and they may hardly gain at all. When they feel better, their appetite revives and their weight catches up with a rush (Spock 2004).

There is no reason to expect your baby to put on weight at a steady rate, week after week, so there’s no advantage in weighing her frequently. Unless there are particular concerns about her health, there’s no need to weigh her more than once a month (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

By exclusively breastfeeding for at least 1 month you have given your baby significant protection against food allergy at 3 years of age, and also against respiratory allergy at 17 years of age (Saarinen. UM and Kajosaari. M).

6 weeks:

Your baby’s second growth spurt will occur around this time.

At this point you may start to notice that your breasts stop feeling so hard and full before each feed, and stay much softer, but fear not, they are actually producing more and more milk for your growing baby. Don’t assume you’re running out because your breasts are softer between feeds: your body is simply becoming more efficient. In fact, between feeds your breasts will probably feel like they did before you were pregnant (Rapley and Murkett 2012). It is unfortunate that this change often occurs at the same time as the 6 week growth spurt, which naturally leads mothers to be unnecessarily concerned about their milk supply. “A baby can still get 180ml (6fl oz) or more from a breast that to the mother does not seem at all full” (Spock 2004).

It’s common at this point to notice that one breast is producing more milk than the other or is easier for your baby to latch onto.

Leaking is likely to have diminished or ceased altogether now, although some mothers experience leaking longer than others.

You may no longer feel your letdown reflex or the feeling may have diminished in strength. Some mothers never feel let-down at all, but they can tell by watching their baby’s pattern of suck and swallow when their let-down is occurring.

It is not recommended that you start expressing until you have had a chance to build up a good milk supply. This usually happens at around 6 weeks. If you decide to start pumping, be aware that pumping only small amounts is not an indicator of a low milk supply.

Likewise, this is the earliest you should introduce a dummy. However refraining from dummy-use altogether is preferable.

By now you will have eased your baby through the most critical part of his infancy. Newborns who are not breastfed are much more likely to get sick or be hospitalized, and have many more digestive problems than breastfed babies. Also breastfeeding for 6 weeks means that your child now has less risk of chest infections up to 7 years old (NCT).

2 months:

Your baby will still need to feed about every two to two and a half hours, although he may go three hours. The normal range is anything from eight to twelve feedings in twenty-four hours (West 2010).

Your baby may now spend less time at each nursing session because he has become more efficient at the breast and therefore requires less time to milk it effectively (Rapley and Murkett 2012). He may also only need to nurse one side per feeding, rather than both sides as he may have done before. Always offer the second side but don’t worry if your baby doesn’t seem to want it or need it.

At this point, most babies, whether breast or formula-fed still need to feed once or twice during the night.

“By month 2, babies’ mouths are much bigger so they find it easier to latch on” (Cave and Fertleman 2012). Consequently, you may find that any over-supply or latching problems begin to correct themselves naturally around now.

From now until 4 months old, your baby should nurse at least 6 times per 24 hour period.

If you choose to get your baby vaccinated they will have their first vaccination around now. By breastfeeding you are enhancing your baby’s antibody response, strengthening the effectiveness of the vaccine (Silfverdal. SA et al). Nursing during the vaccination process will also offer your baby a unique level of pain relief (Tansky.C and Lindberg. CE).

Perhaps you’re noticing that your baby looks slimmer than their formula fed peers? Studies have shown that breastfed babies become noticeably leaner beginning around 2–3 months in comparison to formula-fed babies (Kramer et al., 2004).

By breastfeeding exclusively for 2 months, your child now has a lower risk of food allergy at 3 years old (NCT).

3 months:

Another growth spurt, hang in there. Don’t be tempted to give formula (or even worse, solids) to appease your baby’s appetite, because a decrease in the frequency of nursing would reduce your milk supply, which is the exact opposite of what your baby is ordering.

Even after the growth spurt has passed, a baby between three and four months old should be feeding at least every four hours during the day.

Some babies at this age, because they have become experienced feeders, will nurse for only five or seven minutes, or even as little as two or less per feed (Gonzalez 2014).

If your baby is beginning to give up his night feeds, you will find that he nurses longer at his day feeds.

At this age, your exclusively breastfed baby may go for ten or twelve days without pooping (Gonzalez 2014).

Your breastfed baby will tend to need much less burping now.

Interesting fact: If you are exclusively breastfeeding, your milk is currently providing 535 calories, 6.8g of protein and 37g fat for your baby per day! (Thompson 2012).

You’ve probably heard the delicious fact that breastfeeding uses up the fat stores you laid down in pregnancy. The greatest weight loss is seen in the three to six month period (Moody et al). You’ve just hit the start of this uber fat-burning period.

You may find that your baby becomes more distracted during feeds now. This is because her eyesight has developed and she can see across the room. When your baby seems distracted, take care that this doesn’t mark the beginning of a habit developing when your baby feeds less and less during the day, then makes up for it at night.

Are you finding that your baby is sleeping better at night now? At three months, nocturnal sleep is actually increased in breastfed babies compared to formula fed babies due to tryptophan in breast milk which acts as a regulator (Cubero et al 2005).

By breastfeeding for at least 3 months you have given your baby a 27 percent reduction in the risk of asthma if you have no family history of asthma and a 40 percent reduction if you have a family history of asthma (Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center).

If you have exclusively breastfed for this long, your baby will have enhanced development in key parts of the brain compared to other children who were fed formula or a combination of formula and breastmilk (Dean et al).

By this stage you have also given your baby between a 19 and 27 percent reduction in incidence of childhood Type 1 Diabetes (Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center).

4 months:

By giving nothing but your breastmilk for the first four months you have given your baby strong protection against ear infections and respiratory tract diseases for a whole year (American Academy of Pediatrics; Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center; Duncan.B et al).

By breastfeeding for at least 4 months you have reduced your baby’s risk of SIDS (Mother & Baby).

By now you have overcome early obstacles such as engorgement, sore nipples, and marathon cluster feedings. Nursing is becoming so much easier than bottle-feeding.

Around this time teething may cause your baby to begin drooling, sucking on his fingers, or chewing on objects. This need to suck or chew on things can easily be misread as a sign that your baby is still hungry after a feed and ready to wean. Also, bear in mind that reaching for food is NOT asking for it. Babies reach for everything, and they like to mimic as well, so doing mouth movements also does not indicate a readiness for solids. Likewise, some of your friends, baby food manufacturers and even health professionals may suggest that you introduce solid foods around now. The UK Department of Health, WHO and Unicef all recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months (meaning only breastmilk). This is because your baby’s digestive system is unlikely to be sufficiently developed to cope with solids before then. Also contrary to what some health visitors may contend, starting solid foods before 6 months of age will not increase your baby’s caloric intake or provide a health advantage to your baby. Breastmilk has a higher concentration of fat and other essential nutrients than any solid food.

From now until 7 months old, your baby should nurse at least 5 times per 24 hour period. One of these is likely to be a night feed.

Some babies will want to nurse more often while teething while others may nurse less often, some even refusing to nurse completely, often referred to as a nursing strike. If this happens, try applying infant teething gel. Your baby might accept the breast more readily if her gums are numbed. If your baby still refuses the breast, you will need to pump your breasts frequently to prevent blocked ducts and maintain your supply. A nursing strike will usually last between 2-5 days although can last longer.

You may notice a further slowing of your baby’s weight gain around now. Between four and six months, breastfed babies tend to gain weight slower than their formula-fed peers, although growth in length and head circumference are similar in both groups (Moody et al). “Gradual weight gain, although this is not necessarily even, and a dropping-off of weight gain should not be taken in isolation to suggest that feeding isn’t going well” (Johnson).

Some babies nurse very quickly at this age (3-5 minutes) and may become distracted at the breast, maybe even pulling off the breast after only a few sucks. Feeding in peaceful surroundings can help. Night waking may begin again or become more frequent as your baby tries to make up calories missed during the day (read more about sudden night wakings at 4 months here).

By breastfeeding for 4 months you have given your child a lower risk of developing eczema and asthma (NCT).

By 4 months, babies have entered a significant cognitive milestone; their brains are going through an enormous growth spurt, which accounts for all of the increased alertness and distractibility. A baby who used to feed intently will now pop off and on the breast, turning to look when Daddy or big sister walks into the room or if a noise catches her attention.

You may be preparing to return to work, and lots of breastfeeding Mothers make the decision to switch to formula at this stage. However this does not have to be the case. Your milk can be expressed for your baby to have while you’re at work. You can find a collection of resources for working and pumping Mothers here. If it is not possible to express, try a milk bank or as a last resort you could wean her onto formula during the day and keep her morning and evening breastfeeds going.

Babies tend to want to breastfeed more often when they are feeling emotionally unsettled. If you are returning to work it may trigger increased feedings (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

5-6 Months:

You have greatly reduced your baby’s risk of developing allergies by waiting until at least now to introduce solids, this is particularly the case if you have a family history of allergies.

By breastfeeding for this long you have protected your baby’s intestinal tract so that it can now begin to produce antibodies. These antibodies coat the intestines and protect him from foreign proteins and allergens.

Continuing to breastfeed alongside the introduction of solid foods not only ensures good nutrition, it actually helps with the digestion of those other foods (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

If you are babyled weaning your baby will continue to have ‘breastfeeding poo’ (runny and yellow) with occasional bits, for several months after she has started exploring solids (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Unless your baby is having other drinks (which would decrease her need for breastmilk as a drink), the number of breastfeeds she asks for probably won’t change noticably at first; she will still carry on asking for them in her usual way but take slightly less milk at each feed.

Your baby should still be having at least 6-8 breastfeeds per day (Fredregill 2004).

At around 6 months your baby will experience another growth spurt. Although you have solids to give, remember to offer the breast first as breastmilk is more nutritious. If your baby has been sleeping through the night you may find that he begins to wake for a midnight feeding during this growth spurt.

After the first six months, breastfed babies tend to be leaner. Compared to their formula-fed friends, breastfed infants gain an average of one pound less during the first twelve months. The extra weight in formula-fed infants is thought to be due to excess water retention and a different composition of body fat (Dewey. K). Expect your breastfed baby to gain an average of one pound (1/2 kilogram) per month from six months till he is one year old.

There is no need to weigh your baby more than once every two months now (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Your baby will grow around one-half inch per month from six months to one year.

Keep an eye on your baby’s fluid intake during this time. If too many nursings are replaced by solid feedings too quickly, he may not be getting enough fluid which can lead to constipation (evident in small pellet-like stools). Putting your baby to the breast frequently should alleviate the problem.

A lot of childcare manuals suggest that your baby should have doubled their birth weight by now, but remember that each baby is unique. When evaluating your baby’s overall growth pattern, your baby’s birth weight, length, gestational age, and parental size need to be taken into account. It has been noted that, “by the time they are ready for solids breastfed babies are often gaining less than many of the growth charts say they should” (Lim. P). The complex nature of a harmonious breastfeeding relationship cannot be weighed, measured, or plotted like scientific data on a chart. If you receive overreaction about your baby’s weight from family or health professionals, direct them to this article: ‘Look at the Baby, Not the Scale’.

If you have exclusively breastfed to this point, your baby is more likely to accept a range of solid foods. This is because breastmilk exposes babies to the flavors of their mothers’ diets and serves as a ‘‘flavor bridge’’ between a milk-based diet and a more adult-like diet (Mennella and Beauchamp, 1996; Taveras et al., 2004). Not only is food acceptance higher in breast-fed babies, they are particularly more likely to prefer vegetables (Sullivan and Birch, 1994). What’s more, food rejection or ‘pickiness’ is lower among pre-school children who were exclusively breastfed (Shim et al.,2011), so your child will reap the benefits for years to come!

By breastfeeding for 6 months you have given your baby significant protection against eczema during their first 3 years (Chandra et al).

You are now in the 1% of Mothers who have breastfed for this long! Bravo! (BBC 2012).

You have also given your baby a 19 percent decrease in risk of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia and a 15 percent decrease in the risk of acute myelogenous leukemia (Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center).

7-8 months:

Distraction at the breast may continue. Don’t be misled into believing that your baby’s temporary lack of interest in breastfeeding is a sign he is ready to wean. It is extremely rare for a child to self-wean before one year of age.

You’ll notice that your baby asks for some milk feeds a little later than usual now, especially after a meal where she’s eaten quite a lot of solid food (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Your baby should still be having 5-7 breastfeeds per day (Fredregill 2004).

Your baby will likely be teething in earnest at the moment. There are really two kinds of teething: chronic teething and acute teething. Chronic teething is ongoing. You’ll notice your baby doing lots of drooling, putting just about anything he can fit into his mouth, and gnawing on his fingers or hand. But he will continue to eat and drink normally. During acute teething, a tooth is actively cutting through the gum, which is a very painful process for most children. Babies who are cutting a tooth are often less interested in the breast, or eating solids, as their gums feel sore and irritable when sucking or eating. Luckily, acute teething will only last a few days at a time.

Babies breastfed for between seven and nine months have higher intelligence than those breastfed for less than seven months (Johnson).

9 months:

You have now seen your baby through the fastest and most important brain and body development of his life on the food that was designed just for him – your milk. You may even notice that he is more alert and more active than babies who did not have the benefit of their Mother’s milk.

Some babies display waning interest in the breast around now. This may be due to altered taste brought about by hormonal changes during your menstrual period (if it has returned yet) or a temporary loss of appetite due to a cold or teething. Gentle perseverance is recommended. Try nursing in peaceful surroundings or when your baby is sleepy. If all else fails, pump milk to give to your baby in a cup whilst continuing to offer the breast.

Your baby should still be having 4-5 breastfeeds per day (Fredregill 2004).

Around now, your baby may be mastering the use of a sippy cup, which could lead to further loss of interest in nursing.

If you have been baby-led weaning, your baby will only now be making the connection between hunger and solid food. As she begins to eat more, her poos will start to become more solid, darker and smellier – especially once she starts to cut down her intake of breastmilk (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

Once she is regularly eating and drinking at mealtimes, your baby may decide to skip some breastfeeds altogether, turning away when she’s offered the breast. All you need to do is respond to her cues, just as you have until now. Even if you notice a fairly consistent drop in breastfeeding, it may not be a permanent change. It’s common for babies to go back to breastfeeding for short periods, especially when they are teething or fighting off an infection. They may want nothing but breastmilk for a week or two, then switch back to eating solid foods and taking less milk. Your breasts will adapt within a day or two – even if your milk production has already gone down.

10 months:

Your baby’s increased mobility through cruising, crawling or shuffling may mean that his nursing patterns become erratic. On some days he may so ‘busy’ that he almost forgets to nurse. On such days, periodically offer your breast even if he does not at first indicate a desire to nurse. On other days, when exploration becomes overwhelming, he may nurse almost constantly.

Even though your baby is eating solid foods, breastmilk is still the most important part of his diet, and continues to provide him with important immunities at a time when he is crawling around and putting EVERYTHING in his mouth.

1 year:

Many of the health benefits this year of nursing has given your child will last his entire life. He will have a stronger immune system and will be much less likely to need orthodontia or speech therapy.

Breastfeeding doesn’t have to end just because your baby is no longer relying on it for their sole nourishment – it can carry on for several more years, if you both want.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends nursing for at least a year, to help ensure normal nutrition and health for your baby.

New research suggests that gut microbiota is not – as previously thought – stable from the moment a child is a year old. Rather, important changes continue to occur right up to the age of three. This probably means that there is a ‘window’ during these early years, in which intestinal bacteria are more susceptible to external factors. Even more reason to continue providing invaluable antibodies via your breastmilk! (University of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen 2014).

As you have been lactating for a year, the fat and energy content of your breastmilk has significantly increased compared with the breastmilk of women who have been lactating for shorter periods (Mandel. D et al; Williams 2013).

Is your baby still slimmer than their formula-fed peers? Don’t worry, this is perfectly normal (and healthy!) By the end of the first year, formula-fed infants in affluent countries are 600–650 g heavier than infants breast-fed for 12months (Dewey, 2001).

Many babies continue feeding two to three times a day – perhaps first thing in the morning and last thing at night, plus odd times when they fall over or are tired or upset. Some babies continue feeding ten or so times a day! All normal (Gonzalez 2014).

The fact that most babies can tolerate cow’s milk after one year does not mean that cow’s milk should necessarily replace your breastmilk. Cow’s milk does not contain the bioavailable vitamins and antibodies found in breastmilk. Also it is well documented that the later that cow’s milk (a common allergen) is introduced into the diet of a baby, the less likelihood there is of allergic reactions (Ponzone. A).

If you want to carry on weighing your baby, once every three to six months is more than sufficient from now on (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

As a result of receiving your breastmilk for at least a year your child is more likely to display better social adjustment when they begin school (Kneidel. S).

By breastfeeding for a year you have given your child a lower risk of becoming overweight in later life and lower risk factors for heart disease as an adult. Oh, and you’ve saved yourself at least $720 on formula! (NCT).

16 months:

You have continued to provide your baby’s normal nutrition and protection against illness at a time when illness is most common in other babies. Your baby will continue to receive those important immune benefits for as long as he continues to nurse.

Breastfeeding toddlers between 16 and 30 months old have been found to have fewer types and shorter duration of illness and to require less medical care than their non-breastfeeding peers (Gulick. E).

Some of the immune factors in your breastmilk will increase in concentration during this second year (Goldman. A et al).

Your toddler will now be very quick and efficient at breastfeeding, and able to latch on from virtually any angle.

2 years+:

The World Health Organization and UNICEF strongly encourage global breastfeeding through toddlerhood: “Breastmilk is an important source of energy and protein, and helps to protect against disease during the child’s second year of life.”

“At around two or three, children often experience a sort of feeding frenzy when they want to nurse all the time, sometimes every fifteen minutes. It is almost as if they are ‘play-nursing’. There is no need to worry” (Gonzalez 2014).

Your milk is still providing your child with essential proteins, nutrients antibodies and other protective substances and will continue to do so for as long as you continue nursing. Human biology is geared to a weaning age of between 2 1/2 and 7 years (Dettwyler. K). “It takes between two and six years for a child’s immune system to fully mature. Human milk continues to complement and boost the immune system for as long as it is offered” (La Leche League).

Extensive research on the relationship between cognitive achievement (IQ scores, grades in school) and breastfeeding has shown the greatest gains for those children breastfed the longest (van den Bogaard, C. et al), (NCT) .

At this age many children form attachments to comfort items. This reliance peaks during their second year (Encyclopaedia of Children’s Health; Stringer. K). Examples include rags, toys, dummies and even a bottle, objects that can all be mislaid, forgotten or lost. The beauty of breastfeeding your toddler is that your child’s source of comfort is permanently attached to you. Furthermore, nursing does not produce the harmful health consequences that a dummy or bottle would at this age (e.g. dental malformation, tooth decay, speech delay).

Toddlers like to move. Your toddler has only recently mastered walking, running and climbing, and she loves to find new ways to use her body. Unfortunately, constant motion and breastfeeding don’t go well together. Your little gymnast might decide at some point that nursing would be more fun if he could twist, turn and climb all over you while sucking away. Ouch! Some children can even go from standing to hanging upside down over your shoulder in a single feeding session.

As your child starts to drink less and your production winds down, your milk will become gradually more concentrated – almost like colostrum again – giving her an extra boost of immunity (Rapley and Murkett 2012).

The Alpha Parent